Decades of Service: NROTC San Diego Celebrates 40th Anniversary

It all started with a phone call to Rota, Spain.

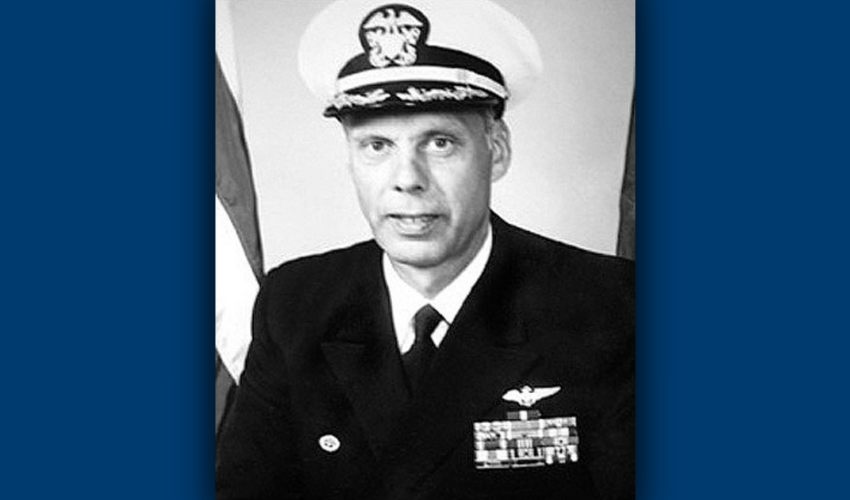

“I got a call from my detailer and they asked, ‘How would you like to be the Commanding Officer and start an ROTC unit at the University of San Diego?’” said Captain Render Crayton. “I said, ‘I’d like that,’ but they said, ‘You’ve got to go back to San Diego and have an interview with the hierarchy of the university.’”

After a flight from Spain to San Diego and an interview with former USD provost Sister Sally Furay ’72 (JD), RSCJ, Crayton found himself with a new job title: Commanding Officer of the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC) San Diego.

The first NROTC San Diego unit launched with humble beginnings in September of 1982 under Crayton’s leadership. The unit started as a partnership between USD, San Diego State University (SDSU), and the United States Navy.

Six scholarship students were enrolled in the program at USD, including a Navy Petty Officer formerly with the Submarine Force, a seaman, and one woman who was a sophomore transfer student from the University of Missouri NROTC unit. Nine scholarship students were enrolled in the program at SDSU.

“I was nervous because I had planned on this being the largest NROTC unit in the country,” said Crayton. “But it took a little time to get the word out.”

NROTC San Diego is now celebrating its 40th anniversary of developing young men and women mentally, physically, and morally to commission as officers within the United States Navy and Marine Corps.

At present, the Battalion has 250 students from USD, SDSU, UC San Diego, Point Loma Nazarene University, and California State University San Marcos. This includes Midshipmen, active-duty Marines participating in the Marine Enlisted Commissioning Education Program (MECEP), and active-duty sailors who have been selected for the Seaman to Admiral 21 (STA-21) Officer Candidate program.

“I just knew it was going to grow because we hadn’t had a unit in San Diego and it was a Navy town,” said Crayton.

That optimism is a trait Crayton has carried with him his entire career in the U.S. Navy, especially when he was taken as a Prisoner of War (POW) in Vietnam.

In February 1966, Crayton was flying a combat mission in an A-4 from the aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga when he was shot down by anti-aircraft fire near the Gulf of Tonkin. Crayton parachuted to the ground and radioed for help. A helicopter was dispatched to rescue him, but couldn’t locate Crayton because he was captured and taken to a POW camp near Hanoi.

He spent the majority of his time in captivity alone. On rare occasions, Crayton would share a cell with one other prisoner.

The cells were stark. Prisoners were surrounded by concrete walls and floors and were given a reed mat and a blanket.

“Believe me, it got cold in Vietnam. It was damp cold in the winter time and those concrete block walls didn’t help at all.”

But those concrete walls were good for one thing — tapping.

Prisoners in the camp weren’t allowed to openly communicate. That meant they had two options: Whisper to one another and risk punishment or utilize what became known as the tap code.

Crayton was placed next to an American who was in the POW camp for three months. He communicated with the man by rolling up his blanket and putting it up against the wall. The man on the other side then used his cup to put it up against the wall to hear what Crayton was saying.

“He told me to look on the wall and see if I could see a five-by-five matrix of letters and I did,” said Crayton. “It became pretty clear what it was.”

The tap code is based on a Polybius square, using a five-by-five grid. All the letters of the alphabet, except for K, which is represented by C, are placed in rows on the grid. There were two rules each American needed to learn to use the tap code: The first knock designates the row and the second knock designates the column.

“It became second nature,” said Crayton. “If you stood outside of one of the buildings, it sounded like a bunch of woodpeckers. We were conversing so fast you wouldn’t believe it!”

Although the Americans found a way to talk back and forth, it wasn’t long before the Vietnamese picked up on what was going on.

“You had to be very, very careful how you used it [the tap code] and you had to have a lookout. The Vietnamese would try to replicate it, so they could trick us into tapping back to them.”

But the initial contact was always the same for the Americans: Tap — tap-tap-tap — tap, to the rhythm of the song “Shave and a Haircut” and then wait for the other person to tap back the “Two Bits.”

“They [the Vietnamese] could never get the rhythm of ‘Shave and a Haircut, Two Bits.’ It was just foreign to their language.”

At one point, Crayton recalls the Vietnamese placing a group of prisoners in one large cell, which brought a reprieve to those in solitary confinement. The prisoners decided to carry out daily activities which included lectures on thermodynamics from a man who was from the Air Force Academy, Spanish, French and German vocabulary lessons, and lastly, movie reenactments from the late Senator John McCain.

“He was a movie fan and he could tell a movie like no one I ever heard. As a matter of fact, he told the movie of Dr. Zhivago. Later on, when I returned to the U.S., I went to the movie with my wife, and about halfway through, I looked over at her and said, ‘I’ve seen this movie before!’ It was because of what John had said.”

Although there were lighthearted moments, there were also times of struggle.

Crayton was moved to a POW camp in Son Tay. The Americans began tapping on the walls to figure out who was the senior ranking officer (SRO) in the camp. When the tapping got back to him, Crayton was designated the new SRO. He says he didn’t have any leadership requirements for the job, but “I had to do what I had to do.”

“I had a bunch of guys who were chomping at the bit to get out of there and I had to calm them down. I also had to convince the Vietnamese to give medical attention to some of the guys that were in really bad shape and keep the Vietnamese from torturing them.”

During the hours that Crayton wasn’t advocating for his fellow men, he’d spend his time remembering math lessons from Georgia Tech and solving problems in his head. When that grew tiresome, he’d watch the geckos on his wall try to catch flies.

“You could watch them for hours and pass a lot of the day because there was nothing else to do.”

By January 1973, word had reached the POW camps that the war was over. The Paris Peace Accord was signed, which included provisions for exchanging Prisoners of War. The plan to bring 591 American prisoners home was dubbed “Operation Homecoming.” Americans began returning to U.S. soil by February and March of that year. Crayton was among them. After seven years of living in the POW camps, quite a bit had changed in the U.S.

“It was a shock. I couldn’t believe all these guys were driving around with hair down to their shoulders, the clothes were different, the way they greeted you was different … it was different altogether.”

Crayton was briefly hospitalized at the Naval Hospital in San Diego for the injuries he sustained overseas before attending SDSU to earn his master’s degree in business in 1976.

“I wanted to go back to school and get used to being in the U.S. again,” said Crayton.

Like many of the military POWs who survived the war, Crayton continued his military career. He served as executive officer of NAS North Island in Coronado, California until 1978 before moving to Newport, Rhode Island to serve as Chief of Staff at the Naval War College.

After that, Crayton studied Spanish at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California before serving as the Commanding Officer of Naval Station Rota, Spain. He served in the role until August 1982 when he returned to San Diego to begin what has now grown into one of the largest NROTC units in the nation.

Looking back, Crayton says he made the right career choice and hopes future generations of sailors and naval aviators feel the same.

“Go enjoy your time in the Navy and stick it out because you’ll never have a career that will give you as much satisfaction.”

— Kelsey Grey ’15 (BA)